Travis G. Cashion

Ritual

January 15, 2020

The order of operations is always the same. We park our trucks at odd angles in the alleyway behind the garage. The radio plays classic rock. We crack open beers immediately upon arrival. In the cluttered garage, with shelves along the perimeter packed with skies, camping gear, and power tools, and where you have to duck in order to avoid hitting your head on the yellow kayak hanging from the ceiling, we pull two folding tables from between the shelves and arrange them in a “T” shape. For cutting boards, two pieces of scrap linoleum countertop, complete with backsplashes, sit atop the tables. Yellow buckets with towels soaking in a warm vinegar solution sit on the ends of the tables. We use these to clean the work surfaces, wipe down the knives, and scrub away any dirt or fur or leaf litter that still clings to the meat. This operation probably wouldn’t pass an FDA inspection, but who cares. It works for us.

I’ve been lucky to find myself in my friend Mike’s dad Gary’s garage at the end of every hunting season for the last several years. That’s where we convene each year to undertake the task of processing the meat we hunted that season. It’s the final leg of the field-to-table cycle, a process that adds up to many hours stretched out over the last several weeks. After this, we’ll each have enough meat to last us until next season, probably even longer. By the end of the night, we’ll hold the final product of all our efforts.

Everyone selects a blade from an arsenal of freshly-sharpened knives. We carve chunks from the shoulder quarters and pile the meat into a large bowl. These cuts are destined for the grinder. We’ll grind them together with pork or beef fat, and a homemade spice mixture to make a variety of sausages: Italian, breakfast, chorizo, or whatever other recipe moves us on the night of preparation. Meanwhile, Gary cuts steaks from the hind quarters. He dismantles each quarter by slicing along the edges of the muscle groups. Then, he carves the larger muscles down into meal-sized portions.

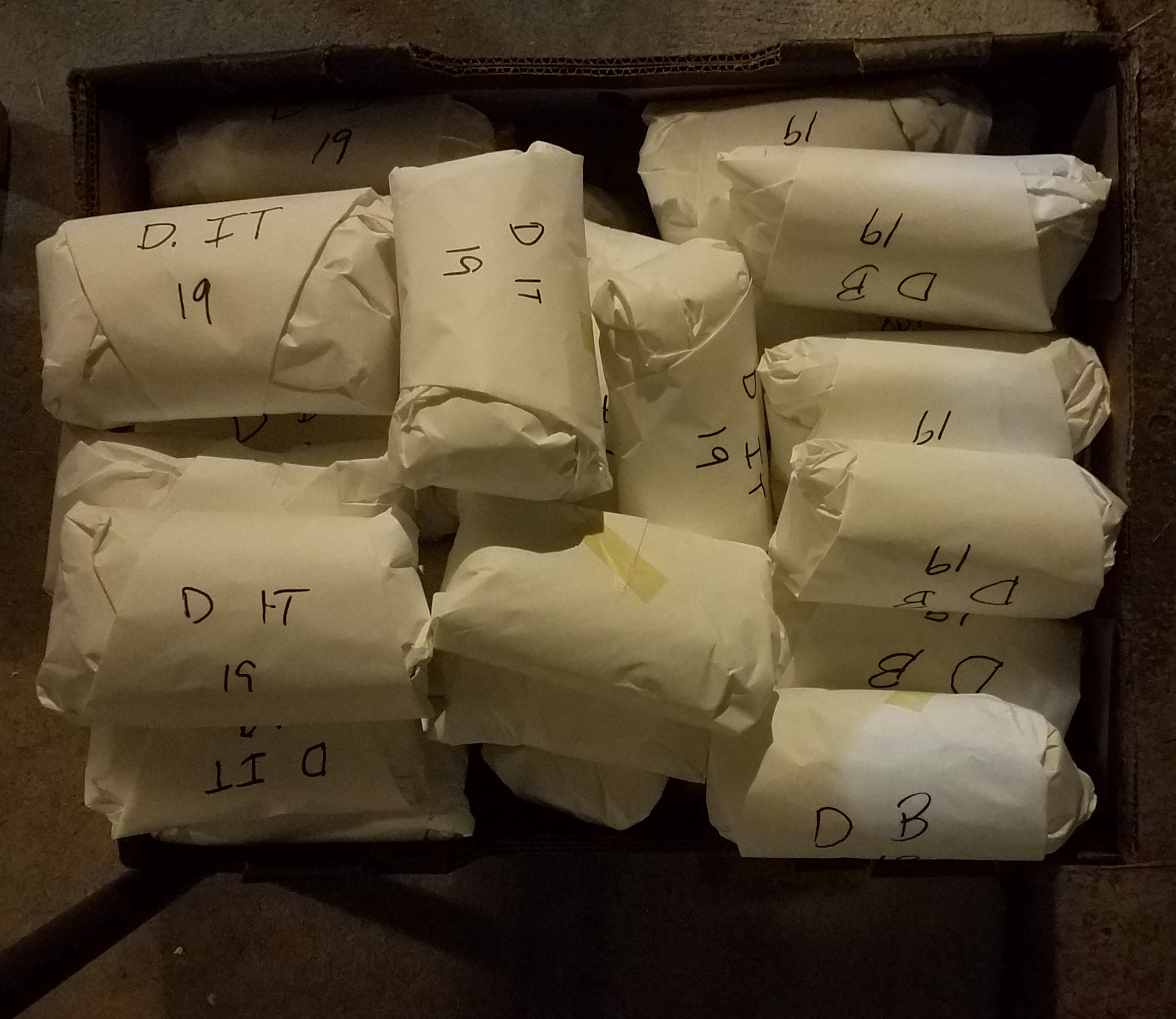

When the are bones clean, we toss a femur to whoever’s dog came along for the night. Then, we form an assembly line and prepare for packaging. Portions of meat roughly the size of my palm go down the line. Each receives an initial protective layer of plastic wrap, then an armor layer of white freezer paper wrapped tightly and sealed with tape. At the end of the line, a black Sharpie stamps each package to demarcate the contents in code. The code describes the hunter, the species, the type of meat, and the year: “M. D. Tenderloin ‘19.” Mike’s deer, tenderloin, harvested in 2019.

The white packages stack up at the end of the table like gold ingots in a bank vault. Greedily, I watch the stack grow. I imagine how my share of the white bricks will look when neatly arranged in pyramid formation in my freezer. At the same time, I gloat to myself about how the quality of this meat is superior to anything else out there. Animals we harvest in the wild feed on wild forage for their entire lives. No antibiotics, no steroids, no artificial grass-fed-and-grain-finished nonsense. We participate in the field-to-table cycle as it unfolds right in front of our eyes. Such direct engagement in provenance elicits a wholesome feeling of fulfillment that is hard to replicate in other pursuits.

With wrapping finished, Gary produces a handful of plastic grocery bags. He always seems to have a ton of these. We make a final tally of the packages, and divide them into piles, one pile per person. Each person who helped hunt, pack out, or process the meat gets a fair share. I fill a few grocery bags with meat and tie the handles closed before lowering them into the cooler in the back of my truck. By the time we’re done, it’s late into the night. Time to go home. With hugs and smiles, we say goodbye to each other.

Nights like this have occurred millions of times throughout the course of humanity: people dismantling the carcass of a freshly-pursued wild animal in order to re-purpose the flesh into food. Our intention tonight is the same as our ancestors’ has always been: to provide clean game meat as sustenance for our families. Our means of accomplishing the task, though, are much different. Instead of using hand-made, stone tools, we employ factory-made rifle bullets and steel knives. Instead of working by moonlight, we work by the light from incandescent bulbs. Instead of hunting out of necessity, we hunt by choice, a choice to carry on the intrinsically human ritual of hunting, and a choice to eat meat earned in the wilderness rather than blindly snagged from a grocery store cooler.