Travis G. Cashion

M.A.F.

March 10, 2019 (ongoing edits and updates)

In 2019, I took up an interest in endurance training when I decided to run my first marathon. It was the Colfax Marathon in Denver, which I ran in May 2019. I learned quite a bit during my training, and put up a decent time of 4:19. Definitely not a record-breaker, but a number I could be happy with for my first long-distance race.

After the marathon, I took several months off running. The desire to run any more after the marathon was completely absent from my mind. Instead, I trained with kettlebells, free weights, pullups, circuit exercises and the occasional session on the treadmill. By this somewhat disorganized approach, I maintained my fitness by showing up to the gym as consistently as possible.

A couple months ago, the lingering complacency with running began to wear off and I started to eye another race this year, which takes place in early August, 2020. Learning about the mechanics of fitness is a huge part of the pursuit for me. This time around, I wanted to take my understanding to an even deeper level. So, a few weeks ago, I ordered The Big Book of Endurance Training by Doctor Phil Maffetone. His big thing is MAF: Maximum Aerobic Fitness. The premise of the book is basically this: your body can burn fuel either aerobically, or anaerobically. Aerobic energy pathways primarily burn fat for fuel. Anaerobic energy pathways burn carbohydrates (in the form of sugar) for fuel. Maffetone says that healthy people and endurance athletes should live mainly in the aerobic zone, because fat stores offer a much more efficient and plentiful fuel source for the body than carbohydrates.

According to Maffetone, the simplest way to tell if a person is training aerobically is to measure their heart rate. Based on a person’s age and fitness level, aerobic training occurs within a calculable range. For me (age 29, moderate fitness level, max heart rate 192), the optimal heart rate per Maffetone’s formula is between 135 - 145 beats per minute (bpm). This means that to increase my aerobic fitness, I should aim to keep my heart rate inside this range, without exceeding 145 bpm, for the duration of my training sessions. If the theory holds truen I should notice that I can run faster and longer while maintaining the same heart rate as my aerobic fitness increases over time.

Think of aerobic fitness as a holistic measurement of a person's overall health. For instance, a guy can be ripped to the gills after years of intense weight-lifting and steroid use. He may appear healthy on the outside, but if he runs out of breath after climbing a single set of stairs (indicating poor aerobic fitness), it's hard to argue that his health is actually in goods shape. If what Maffetone wrote is true, then training with MAF in mind will combat this type of off-balance scenario, ultimately creating an athlete that can perform at high levels with a steady heart rate compared to an unfit person.

The roided-out meat-head that can’t climb the stairs is an extreme example. But, this scenario is sort of where I found myself this winter. I realized after flipping through The Big Book that my aerobic fitness is quite limited, despite my regular trips to the gym. Ostensibly, I look like a healthy and fit person. But if you measure my heart rate while I run around the park by my house, I can barely hit a 13:00 minute/mile pace before my heart rate jumps over 145 bpm. So, with the goal of increasing my aerobic fitness and thereby improving my overall health, I’ll put the MAF theory to the test. That’s the purpose of this post, which will be an ongoing log of milestones in my training.

If you’re reading this, trust me when I say that I’m very happy you’re following along. But, please don’t mistake what I include here as expert training or medical advice. I am only a humble layman on the topic.

That said, here we go:

Training Approach:

My race takes place in August. Until then, I plan to focus intently on building my aerobic base. For the first iteration, I will follow these basic rules:

- Always warm up for a minimum of 12-minutes, gradually increasing heart rate from resting rate to MAF. Cool down length of 12 minutes, as well.

- Train aerobically (inside MAF) for the majority of sessions.

- Alternate with the occasional anaerobic training session, using short HIIT sessions as the primary method. After continuing my research in order to cross-check Maffetone's priniciples, I made the decision to incorporate high-intensity interval training (HIIT) into my plan. This mainly came from what I read in Power Speed Endurance: A Skill-Based Approach to Endurance Training by Brian MacKenzie, and The 4-Hour Body by Tim Ferriss (which heavily includes Brian MacKenzie in the secion about ultra-marathon training). What I gleaned from these sources is that HIIT trains the body to more readily revert to aerobic fuel pathways. In other words, during the “high-intensity” phase, the body burns carbohydrates anaerobically, but during the rest periods, the body reverts to burning fat aerobically. Training the body to switch back and forth like this improves its ability to access aerobic pathways (mechanics of this beyond my expertise).

- Never more than one anaerobic/HIIT session in a row. Alternate days of anaerobic and aerobic training.

- During HIIT sessions, if my heart rate does not return to 120 bpm within 120 seconds of rest, then the session is done (this rule courtesy of Tim Ferriss, 4HB).

Training Milestones:

February 25th: I performed my baseline MAF test on a treadmill. Here are the results:

Initial MAF Test: 145 max HR

- Mile 1 pace: 11:55

- Mile 2 pace: 12:35

- Mile 3 pace: 13:28

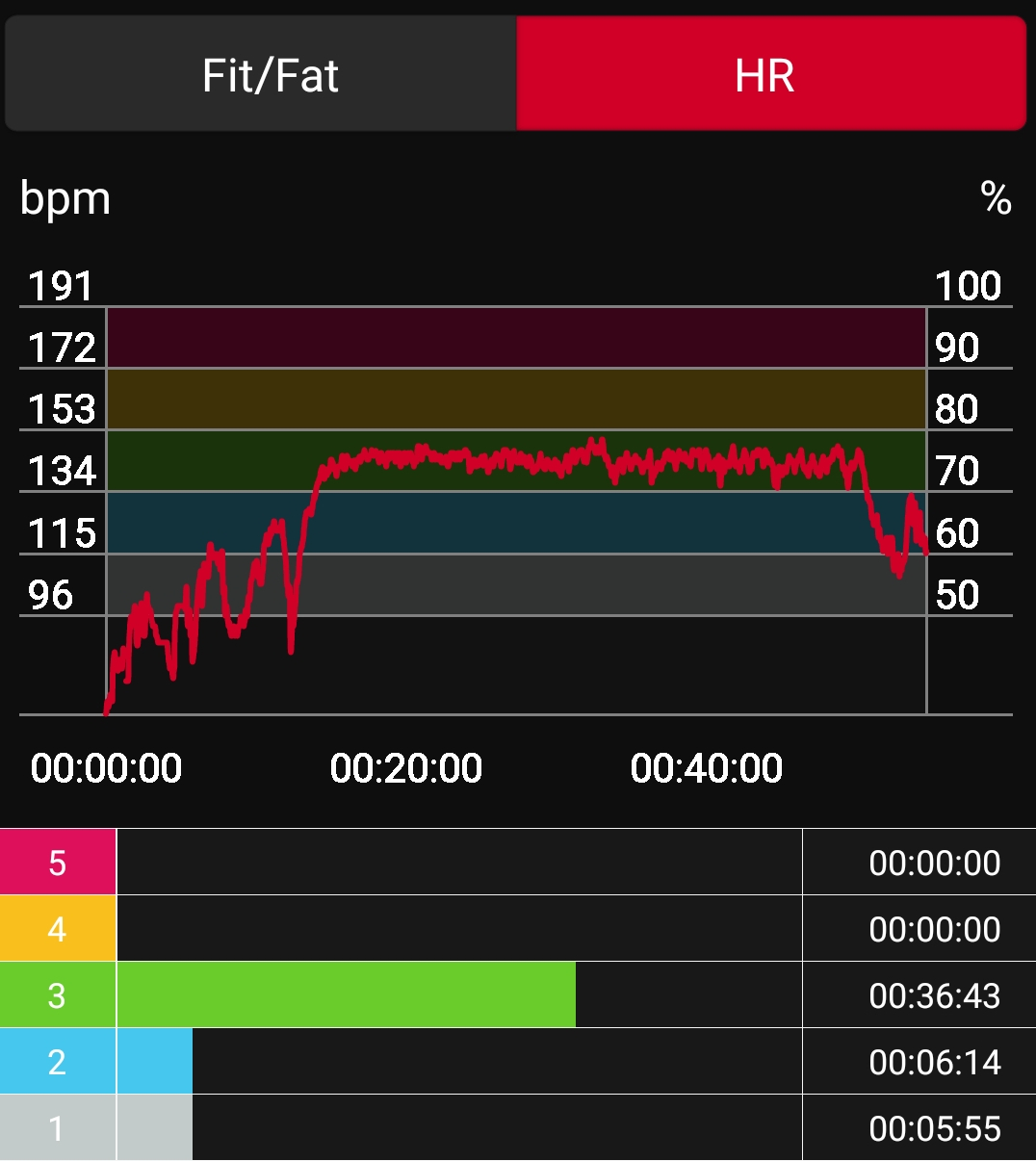

Notes: 12-minute warmup, approx. 12-min cool-down. See heart rate data to the right.

After this session, I trained most days in aerobic fashion with only one or two days of anaerobic training (mainly pullups, to maintain the work I’ve put in over the past few months). For aerobic workouts, I primarily did kettlebell swings with a lighter, 15 lb kettlebell. I found I could do swings with this weight for 10 minutes straight and maintain 140-145 bpm.

March 9th: I did a shorter, follow-up treadmill session to check status.

MAF Status Test: 145 max HR

- Mile 1 pace: 11:25 (30-second improvement since 2/25!)

- Mile 2 pace: data lost (fat fingers hit the “reset” button)

Notes: breathing cadence 3x7 then 3x5 (meaning inhale lasts duration of 3 steps, exhale lasts duration of 7 or 5 steps). I’ve found that a shorter inhale and longer exhale helps me maintain a more steady heart rate. Inhale should always be through the nose when training aerobically.

March 10th: first HIIT training

Notes: kettlebell swings with 35 lbs, 60 seconds on 60 seconds off for 5 sets. See heartrate data to the left.